by Andrea Tucci,

Just over a hundred years ago, Greece and Turkey faced the “Asia Minor Catastrophe,” a dramatic event largely unknown throughout Europe and beyond.

In 1923, with the Treaty of Lausanne, which ended the armed conflict, Greece and Turkey initiated a population exchange that would forever alter the face of both countries.

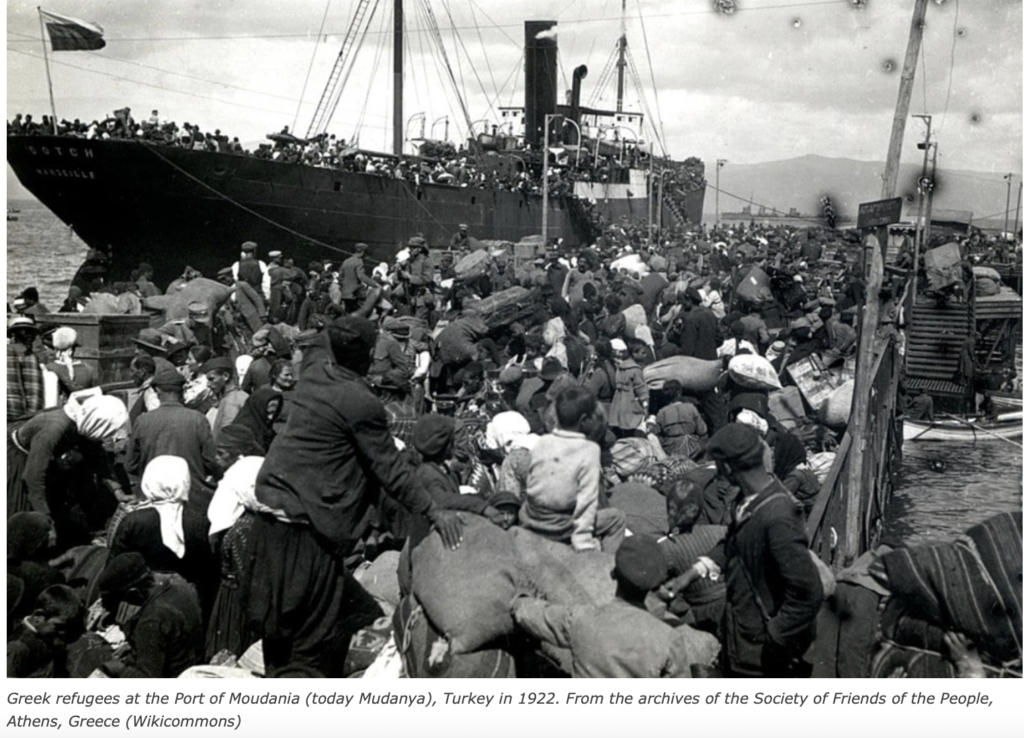

More than 2.5 million people were uprooted and moved across the Aegean, expelled from their homes because they were of the “wrong religion.”

Orthodox Christians were deported from Turkey to Greece, while Muslims from Greece were sent to Turkey. The population exchange involved approximately 500,000 Muslims in Greece and at least 2 million Greeks in Turkey.

The Treaty of Lausanne outlined the terms for this exchange, and Dr. Fridtjof Nansen, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate in 1922, was appointed High Commissioner responsible for overseeing the migration. In Greece, an independent organization led by Mr. Henry Morgenthau, the former U.S. ambassador to Constantinople, facilitated the resettlement of the displaced populations.

Dr. Fridtjof Nansen (Nobel Peace Prize 1922)

The Greek Orthodox population of Turkey was evacuated from three main areas: Constantinople, the western coast, and Trebizond. Their relocation was carried out in various ways. However, the primary challenge was not the migration itself, but rather the resettlement of the repatriated people. Greece received a number of immigrants equal to one-third of its native population, while Turkey received barely one-tenth. Additionally, Greece’s large influx of refugees arrived all at once and without preparation, leading to a significant sociological impact and an economic disaster, which resulted in a prolonged period of internal chaos.

In the case of the Muslim Greeks, mostly evacuated from western Thrace, many were poor and afflicted with various illnesses. Those who survived often found themselves without a means of livelihood—no agricultural tools, no animals, and often no proper dwellings. They were forced to beg while waiting for work that never came.

The distribution of the newcomers seemed to have been done without any coherent strategy. The destination of certain convoys was changed multiple times, and in the assigned localities, nothing was organized. As a result, the emigrants lived inside trains for several months, waiting for a permanent settlement, growing increasingly exasperated.

Most of the repatriated Greek Muslims had to settle for improvised accommodations, where they lived for extended periods.

It was challenging to find similar conditions in the countries they were sent to compared to where they came from. Mountain folk, fishermen, and plains people were all involved, but selecting suitable environments for them in the new country would have required a detailed geographical and demographic assessment, which unfortunately was not done in either Greece or Turkey.

This event is known in Greece as “I megali katastrofì” (The Great Catastrophe) and in Turkey as “The Exchange of Lausanne.” A century later, it still stands as a testament to the social and humanitarian catastrophe that occurred with the Treaty of Lausanne. Even today, both populations still speak both languages, but only a few have managed to rediscover their place of origin and family roots. However, it is certain that the Greek and Turkish people lived together for centuries, not as enemies but as friends, and their common cultural and multiethnic heritage should not be lost. To preserve this, it is essential to remain distant from the politics of both the Athens and Ankara governments.